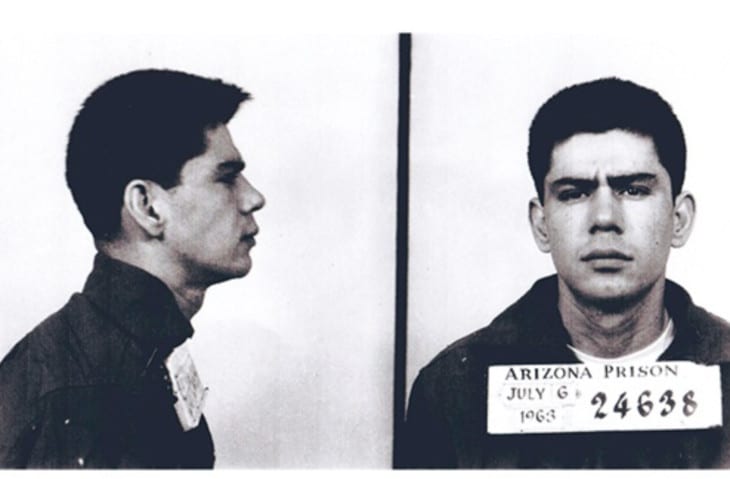

Why Was Ernesto Miranda Arrested?

On March 3, 1963, an eighteen-year-old woman had been working in the concession stand at a movie theatre in downtown Phoenix. After work, she boarded a public bus to go home. When the bus reached her stop, she started to walk toward her house. She observed a car, which afterward proved to be that of Ernesto Miranda.

Mr. Miranda got out of his car, approached the woman, and forced her into the backseat of his car. The woman had never seen Mr. Miranda before.

Mr. Miranda drove the car for about twenty minutes out to a secluded area in the desert. Mr. Miranda stopped the car, and sexually assaulted the woman. Mr. Miranda then drove the woman back into the city. As he dropped her off he told her “pray for me.” The woman ran home and told her family, who called the police.

The woman met with detectives and told them that the car that her assailant drove was green or gray, and had dark upholstery with stripes. About a week later, a family member of the woman spotted a car in the neighborhood that matched the description and got a partial license plate which he provided to police. From that partial plate, the detectives determined that Ernesto Miranda was a suspect.

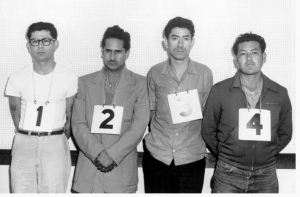

On March 13, 1963, police officers arrested Mr. Miranda and took him to the police station. Officers placed Mr. Miranda in a lineup, but the woman he had kidnapped and assaulted was not able to positively identify him as her attacker.

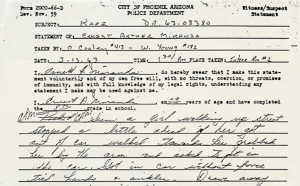

Detectives then questioned Miranda for two hours. The detectives did not inform Miranda that he had the right to have an attorney present.

Mr. Miranda eventually confessed to kidnapping and assaulting the woman, and his confession was used at his trial. The jury convicted him and the judge sentenced him to 20 to 30 years in prison.

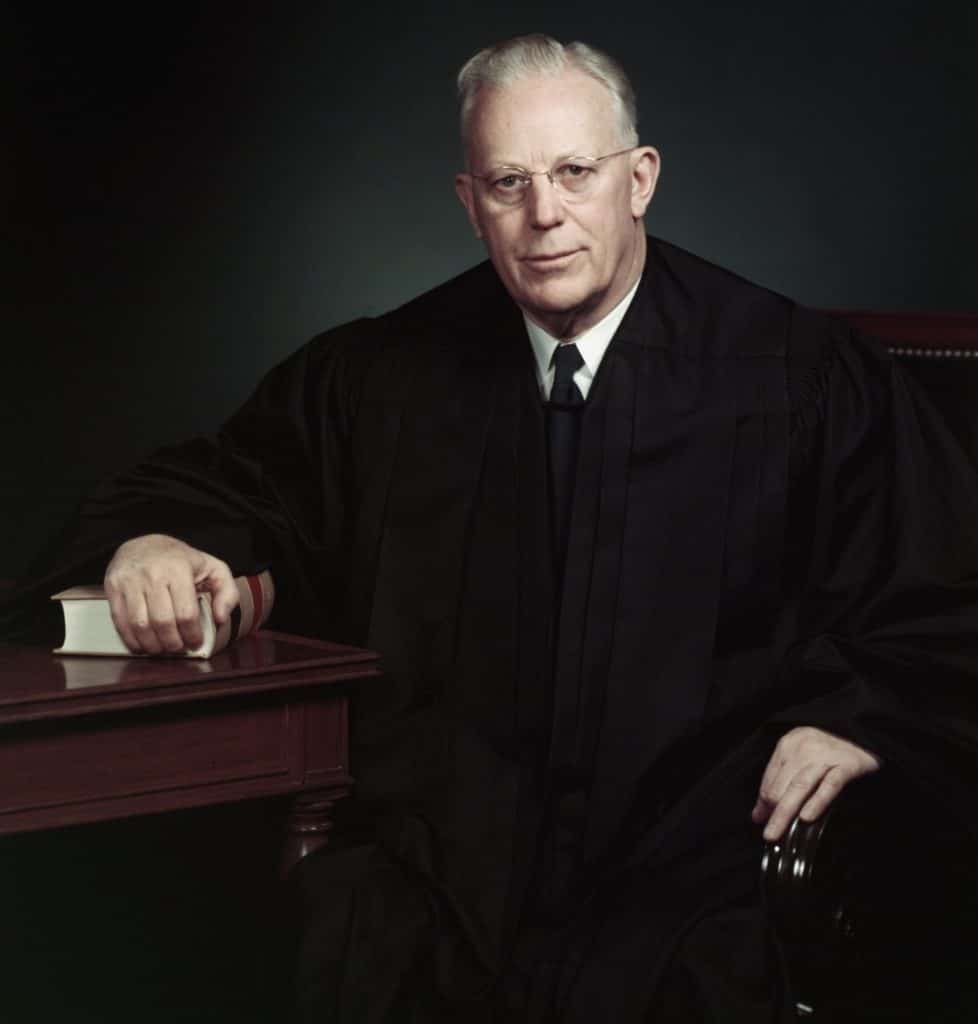

The United States Supreme Court Decides Mr. Miranda’s Case and Establishes the “Miranda Rights”

In 1966 the United States Supreme Court reversed Mr. Miranda’s conviction and ordered that the State of Arizona give him a new trial.

The Supreme Court held that though the Fifth Amendment of the United States Constitution guaranteed that “no person shall be compelled in any criminal case to be a witness against himself,” that when police officers take a person into custody and question them, that the unless the police give the person certain warnings, the officers are essentially compelling the person to be a witness against themselves.

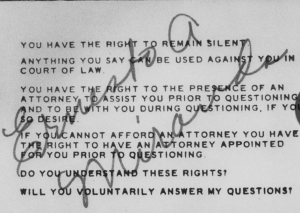

Therefore, the Supreme Court held that when an individual is taken into custody or otherwise deprived of his freedom by the authorities and is subjected to questioning, police must warn the person prior to any questioning of the following:

- that he has the right to remain silent;

- that anything he says can be used against him in a court of law;

- that he has the right to the presence of an attorney;

- if he cannot afford an attorney one will be appointed for him prior to any questioning if he so desires.

Many people misunderstand the Supreme Court’s holding in the Miranda case. Miranda does not mean that police must read a person his rights after any arrest, nor does Miranda mean that police must read a person his rights before any questioning.

Since Miranda v. Arizona, When Do Police Have to Read Suspects Their Miranda Rights?

What Miranda Rights means is that police only have to read a suspect his Miranda Rights if police conduct a custodial interrogation. A suspect is in custody for purposes of receiving Miranda Rights protection when there is a formal arrest or a restraint on freedom of movement of the degree associated with a formal arrest. Interrogation under Miranda refers not only to express questioning but also to any words or actions on the part of the police that the police should know are reasonably likely to elicit an incriminating response from the suspect.

In a custodial interrogation, custody, and interrogation take place at the same time.

Sometimes police conduct an interrogation but the suspect is not in custody. For example, detectives will frequently leave their business cards at the homes of persons involved in an investigation. If the person that received the business card calls the detective and agrees to come to the police station to answer some questions and the detective does not detain or arrest the person during the questioning, there is interrogation but no custody – so the detective is not obligated to read the Miranda Rights.

Sometimes the suspect is in custody but the police don’t conduct an interrogation. For example, police officers frequently arrest two subjects at the same time and place them in the back of a patrol car. Unbeknownst to the two subjects, police will leave a recording device on in the vehicle so they can record what the subjects are talking about. Often, one or both of the suspects will make incriminating statements. The two subjects are in custody but because no police officer is asking them questions there is no interrogation – so the police officer is not obligated to read the Miranda Rights.

When Do Police Not Have to Read Suspects Their Miranda Rights?

Miranda warnings are normally not required under the following circumstances.

- When police stop a driver for a traffic infraction. However, if during a routine traffic stop the police officer puts the driver in custody and then questions him, Miranda warnings will be required. For example, if an officer stops a person on suspicion of DUI and simply asks the DUI suspect where they are coming from and where they are going, Miranda warnings are not required. However, if that same officer were to order the DUI suspect out of the vehicle, handcuff him, and then put him in the back of the police cruiser, then the officer should read the suspect the Miranda rights before questioning.

- During encounters with police in which a reasonable person would feel he or she was free to walk away from the police. For example, if an officer simply walks up to a suspect in a shopping center parking lot and starts casually asking the suspect questions, the officer does not have to read the suspect his Miranda rights. The key issue in situations like this is whether or not a reasonable person in the shoes of the suspect would have felt that he or she was free to walk away from the officer. If a reasonable person in the shoes of the suspect would have felt free to walk away from the officer, then Miranda warnings are not required. If a reasonable person in the shoes of the suspect would not have felt free to walk away from the officer, then Miranda warnings are required.

- During interviews with police in which a suspect voluntarily travels to the police station to speak with officers. For example, police detectives sometimes leave a business card at a suspect’s house or workplace. When the suspect finds the business cared, they frequently call the detective back and arrange to voluntarily meet with the detective. In situations like these where the suspect is agreeing to voluntarily go to meet with the police, the Miranda warnings are not required.

- When the person questioning the suspect is not a police officer. For example, loss prevention employees at department stores frequently question persons that are suspected of shoplifting. Because these loss prevention employees are not police officers, they don’t have to read people their Miranda rights. However, if a police officer were present during the questioning and if the police officer was directing the department store employee how to question the suspect, Miranda warnings would likely be required.

- When the police officer’s questions are not designed to elicit incriminating evidence, even if the questions end up providing incriminating evidence. For example, police officers often ask suspects routine booking questions regarding their age, height, weight, eye color, name, and current address. Questions like these will normally not require the officer to read the Miranda warnings, even if these questions end up eliciting incriminating evidence.

- When the police officers are not actually questioning a suspect, they don’t have to read the Miranda rights. For example, sometimes when a suspect is arrested, they get very nervous and just start talking, even though the police officer is not asking them any questions. In situations like this the Miranda warnings are not required.

- When two or more police officers are speaking to one another in the presence of the suspect, and the officers’ conversation amongst themselves is not reasonably likely to elicit an incriminating response from the suspect. For example, there is a famous Supreme Court case called Rhode Island v. Innis in which Mr. Innis was arrested by police for armed robbery of a cab driver. The cab driver identified Mr. Innis as the robber and claimed that Mr. Innis had robbed him with a shotgun. However, when the police arrested Mr. Innis near the scene of the robbery, he was unarmed. As the officers transported Mr. Innis to jail, Mr. Innis overheard the officers say in conversation to one another that there was a school for handicapped children that was in the area of the robbery, and that if one of the children found the hidden gun, they could hurt themselves. Mr. Innis then interrupted the officers’ conversation and told them to bring him back to the area of the robbery so he could show them where he had hidden the gun. The United States Supreme Court held that the term “interrogation” under Miranda referred not only to express questioning, but also to any words on the part of the police that the police should know were reasonably likely to elicit an incriminating response from a suspect. The Court then stated that Mr. Innis was not interrogated within the meaning of Miranda, because the officers would not have known that their conversation about the gun and the handicapped children was reasonably likely to get Mr. Innis to confess to possessing the shotgun and committing the robbery.

What are Some Mistakes that Police Officers Make when they Read the Miranda Rights?

- Police officers are trained not to make threats or promises in order to get suspects to confess. The reason for this is that confessions that are the product of coercion are simply not reliable, so judges will not allow confessions that are a product of threats or promises into evidence. However, some officers make the mistake of threatening suspects with prison time if they don’t confess. Also, some officers promise suspects that they will go free if they do confess. In situations like these, even though the police may have advised the suspect of his Miranda rights, a judge may decide to exclude from evidence the suspect’s statements.

- Police officers sometimes don’t properly read suspects all of the Miranda Rights. For example, in one case the Hardy Law Firm handled in federal court, an English-speaking police detective used a Spanish speaking police officer to translate the Miranda warnings for a Spanish speaking suspect. However, unbeknownst to the English-speaking detective, the Spanish speaking officer did not translate all of what the English-speaking detective said, and the Spanish speaking officer ended up neglecting to include some of the key parts of the Miranda warnings. All of this was on video, so there was no dispute that the suspect had not received all of his Miranda rights before the officer interrogated him. In cases like these, a judge will likely exclude from evidence the suspect’s statements from evidence because the suspect was not properly given his Miranda rights.

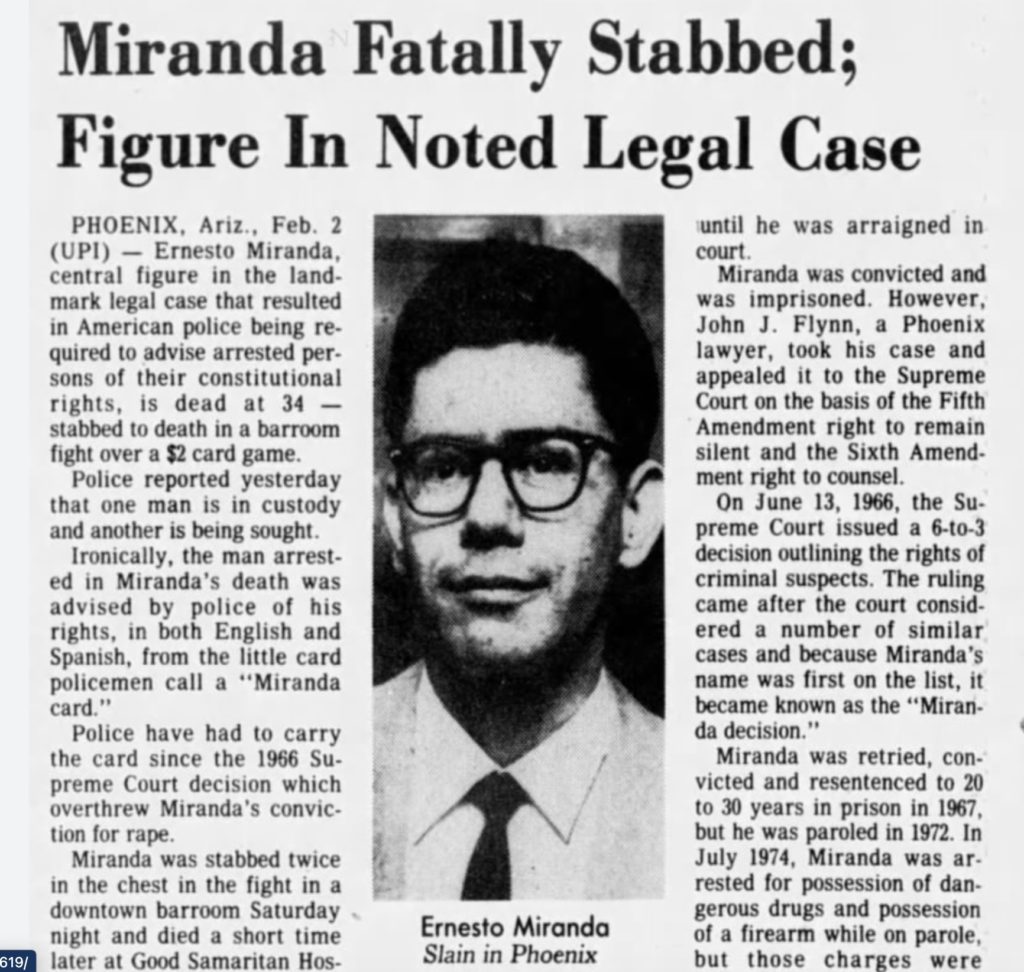

What Did Ernesto Miranda Do After He Was Released From Prison?

As far as Mr. Miranda himself – he did not get away with his crime. After the United States Supreme Court overturned his conviction in 1966, his case was returned to the Arizona trial court. At his second trial, the prosecutor could not use Mr. Miranda’s confession against him. However, Mr. Miranda’s ex-common law wife testified at the second trial that shortly after Mr. Miranda had been arrested for the kidnapping, she had gone to visit him in jail and that during that visit Mr. Miranda admitted to kidnapping and assaulting the eighteen-year-old woman. The jury convicted Miranda, and the judge sentenced him to prison.

Mr. Miranda was paroled in 1973, but his newfound fame made it difficult to get a job. To make money, he carried autographed Miranda Cards and sold them around Phoenix.

How Did Ernesto Miranda Die?

Before too long, he was picked up on a parole violation and sent back to prison. In 1976, he was released but shortly thereafter got into a fight over $2.00 in change during a poker game at a bar. During the fight, Mr. Miranda was stabbed to death. Police detained and questioned a suspect that allegedly had handed the murder weapon (a knife) to Miranda’s killer, but the suspect, after receiving his Miranda warnings, declined to make a statement. The killer fled and was never found.

Know Your Miranda Rights

If police seek to interview you concerning a crime, it’s best to speak with an experienced criminal trial attorney before speaking with them. Though you may be completely innocent, misunderstandings can occur. An attorney can guide you through the process, and safeguard your rights.

If you or a loved one is under investigation in the Tampa Bay area for a Federal Offense or State offense, contact Board Certified Criminal Defense Attorney David C. Hardy.

Posted in Criminal Procedure