Attorney David C. Hardy Files a Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the United States Supreme Court

Posted by David C. Hardy on July 20, 2025

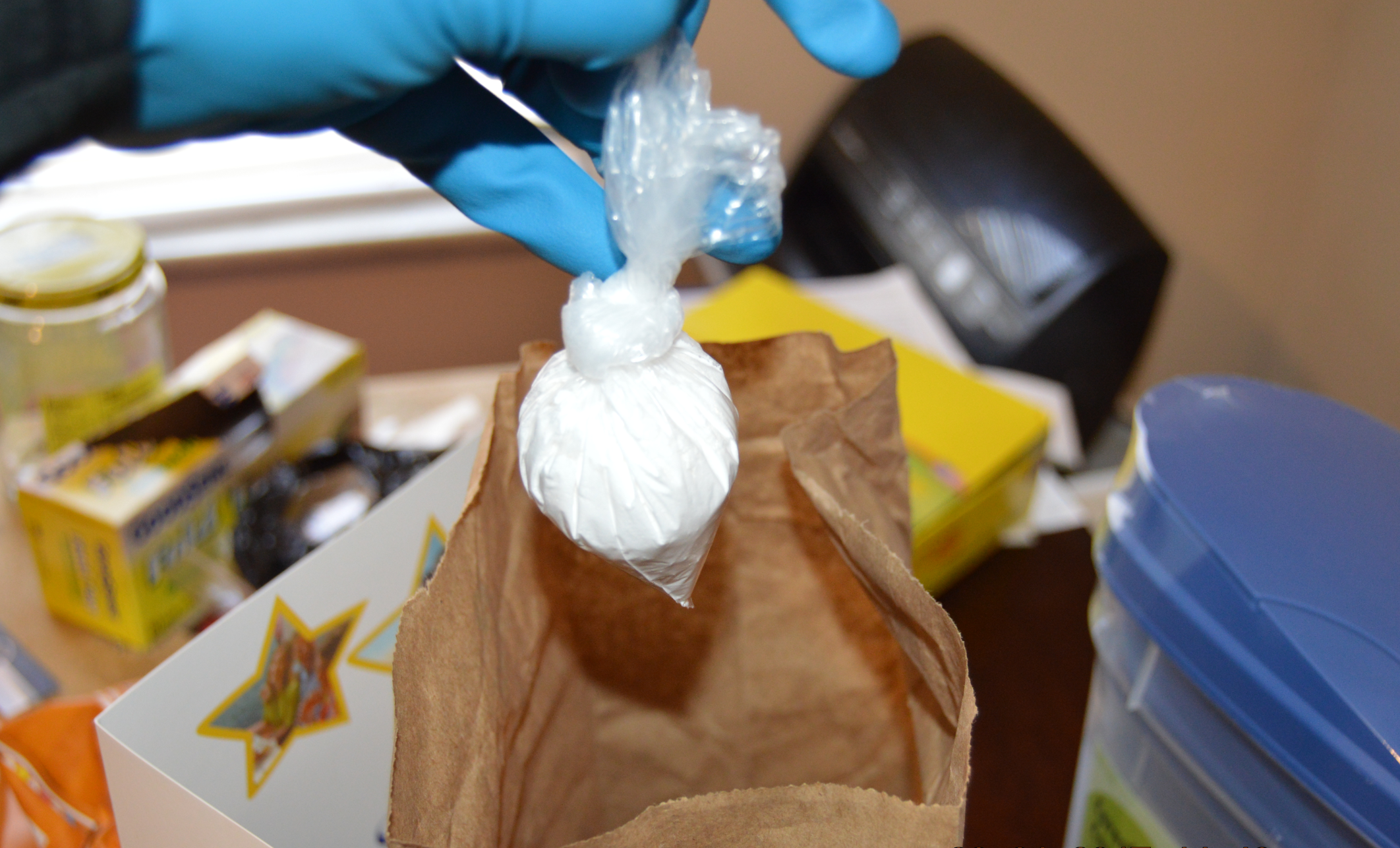

Attorney David C. Hardy has filed a petition for a writ of certiorari in a case involving the Maritime Drug Law Enforcement Act.